Working with a Designer

Posts to help you work seamlessly with your designer or pick up some DIY tricks yourself!

Beginner’s Guide to Finding the Perfect Visuals – Part 2: File Types

Last week we went over how to find illustrations or images that will work for your project, keeping them consistent and thinking about how they’ll work in your design. Now we’re going to talk about the “boring technical” stuff: file types and resolution. (Actually, I don’t think it’s boring or super-technical, but I get that most people sort of do.) While you can always ask me directly if an asset is going to work before you purchase it, it helps to keep this information in mind while you’re searching, so you’re not saving different items that are not a good fit for how we plan to use them.

This month I’ll be spending some time going through some basics and resources as well as a sample visual search with some effective techniques. Catch the whole series here!

Illustration or Image?

First, let’s clear up some quick terminology. Let’s say you’re looking at a beautiful painting of a rose or a line drawing of a famous landmark. Someone drew it, so it’s an illustration, right? Not necessarily. The item could have been drawn or painted and scanned in or it could have been created in a digital illustration program. (Or it could have been scanned in and then digitized in a program.) The file type is going to determine how we can use each asset, so read the following sections and then look for the file types mentioned to decide if it’s the right fit for your project.

Illustrations

Let’s talk illustrations first, because they’re more confusing to most people. An illustration is most generally going to be a vector file, which means it’s created by a series of lines, curves, and points that define the edges of shapes. (If you’re flashing back to high-school geometry here, you’re not alone, but don’t panic.) Vectors are infinitely scalable, so you could use the same visual on a postage stamp and a billboard.

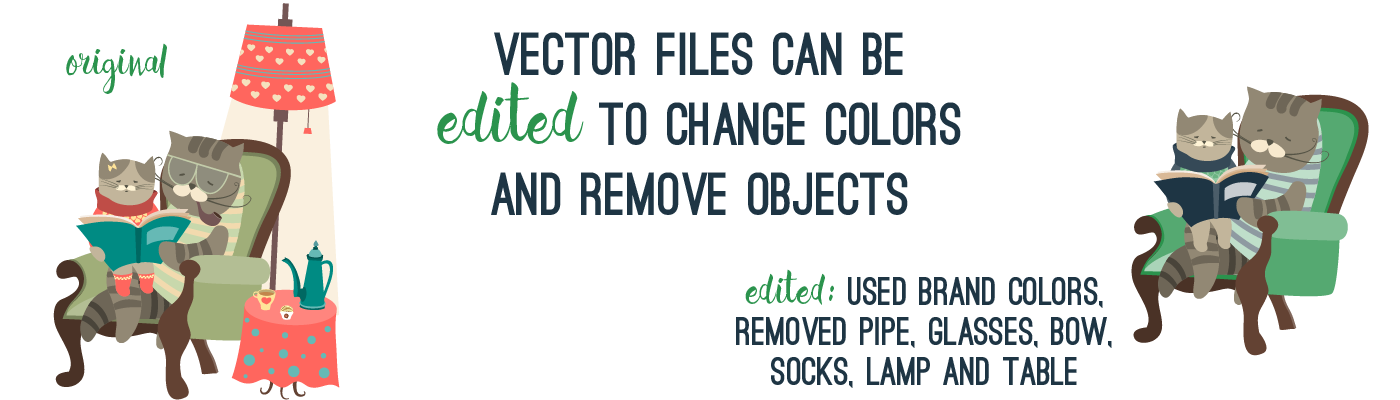

As we discussed last week, illustration files are generally much easier to recolor and make composition edits to. If the illustration is of a scene with a figure in it, things can usually be taken out or moved within the scene (as opposed to moving a figure from one side of a photograph to another).

The file types you’re going to want to keep an eye out for when it comes to illustrations are EPS, AI, and PDF. These files mean that the shapes that make up an illustration can be edited (changing color, filling with pattern) and scaled. These files can contain non-scalable elements, but that’s pretty uncommon for stock visuals available for sale. SVG files are also vector, but they are somewhat unusual on stock sites and they can be tricky to edit. AI files are the primary file format of Adobe Illustrator, so if an asset’s description mentions Adobe Illustrator files, they are most likely vector.

Some illustration assets will be packaged with images files as well (we’ll get into that in a minute), but as long as you see EPS, AI, or PDF, you will be getting what you need. Most computers don’t software installed that will open an EPS or AI file, so don’t panic if you download assets and try to check them out and get an error. You should be able to view a PDF using Adobe Reader (a free program, you almost certainly have it).

Images

Picture files are a fixed size and can always be made smaller but can’t be scaled larger without loss of quality. Images can come in a variety of file types and the file size (in kilobytes or megabytes) isn’t necessarily an indicator of physical size the image can be reproduced at.

Picture file types can be JPG, BMP, PNG, or TIFF. PNG and TIFF support transparency within the file, so they’re a popular format for a series of individual elements that are ideal for layering, like watercolored flowers.

When it comes to these file types, image dimensions are important. (For more of an explanation of what image dimensions are, check out this post!) The listing should probably indicate the file dimensions, it will likely be listed as [one number]x[another number] (and will occasionally use “px” to mean pixels). If you intend an image to be used for print, dividing these numbers by 150 will give you the maximum size in inches that an image can be produced. So 1500×3000 would be 10 inches by 20 inches. (For high-quality press work, printers prefer the numbers to be divisible by 300 or even 600, but 150 is the very lowest size you can print at and still have it look reasonably good.) If you know an image needs to be used on posters or signage, keep in mind that these dimensions make restrict how the picture can be used.

Listings may also say that an image is 300 dpi (or some other number), which is helpful to know, but not as important as the actual dimensions themselves.

Print or Web?

When buying images, there will sometimes be options to purchase for print or web (or web, small, medium, or high resolutions/sizes). Larger images are generally priced higher and you may look at the dimensions of a smaller image and decide it works for you for this project. I’d encourage you to always purchase the largest image that your budget can handle, however. Building an asset library for both the immediate project and future projects is very valuable for most businesses. You may not have intended to have print materials for your event, sending only digital invitations and social media advertising, but then decide you need some signage at the event. A small-sized image is going to be very difficult to work with on large-format print pieces, so paying for the bigger image the first time will have served you well here. Additionally, you may decide 6 months from now that you’d like to use an image on the full page of an annual report or printed on a trade show display. Fill your library with the most useful versions of every asset you purchase!

Thanks for sticking with me on this topic, I know it can be dry, but it’s important. Next we’re going to talk about some great places to search for assets, both free and paid, and how to find deals.

0 Comments